After celebrating Doctor Who last issue, how about a game that pays tribute to the full spectrum of bleak and cheerful 20th Century British sci-fi? Australian solo developer Luke Miller tells us all about his Liberation.

After celebrating Doctor Who last issue, how about a game that pays tribute to the full spectrum of bleak and cheerful 20th Century British sci-fi? Australian solo developer Luke Miller tells us all about his Liberation.

When people talk of British sci-fi of the 1980s, video games are rarely part of the conversation, but you obviously believe there’s much that ties them together?

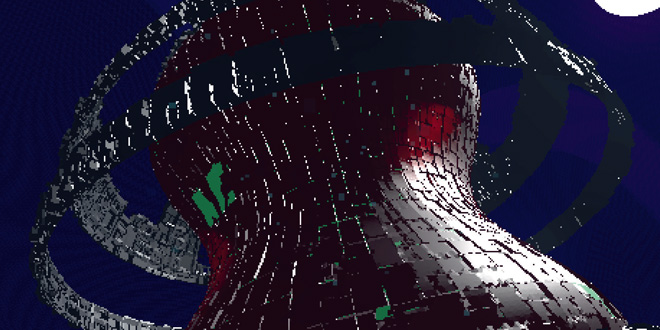

My subconscious went there before I had a clear explanation for what was calling me to make this game [Liberation]. I knew I wanted to make “my version of Elite”. I knew it had to have an Amiga retro computer flavour. I had a strong drive to push it towards Blake’s 7 and something was inexplicably telling me to make it as metal as possible even though I’m more of a synth-pop person. So for the first half of developing an Elite-style space game I was like “Why? Why? Why am I thinking Beano? Why am I thinking of Robots of Death? Why am I thinking Judge Dredd and Christopher H Bidmead?”

I was fighting it until I had a moment of clarity – that entire body of work (books, movies, TV, games, comics, audio and even the hardware) are all in the same thematic universe. Think about it … it was mostly created by people who grew up at the same time in the same part of the world with the same values and influences. On a cosmic time scale they’re basically the same person. Even the UK hardware scene at the time is part of it. Someone would be designing the ZX Spectrum in the morning, their friend would be writing the word processor software in the afternoon, their cousin would be writing a fanfic of The Tripods on it that evening and their next door neighbour would be writing a game based on that fanfic the next day.

It’s a complete ouroboros you rarely get in history. To the point the BBC Micro computer was even on screen as part of the TARDIS console in the 1980s. Douglas Adams not only wrote Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, but also did a BBC TV and a video game version. You can’t separate any of it.

We focus on the technical brilliance of Elite but rarely on the cultural and artistic side of it. Apologies for the essay but I get really excited about it.

What is it about the sci-fi of that particular place and time that appeals to you?

On a production level, I love how simultaneously shit and brilliant it is. If you turn on an old episode of Doctor Who, the roundels (yeah, I know what they’re called) are FILTHY… but it’s still a time machine from another world. I find that relentlessly fascinating. All the BBC videotape sci-fi from that period is similar. The Liberator set in Blake’s 7 is literally falling apart by episode 10. The video camera in Survivors is so degraded there’s a green line down the left side of all the footage in season 3. In Star Cops the actors have to pretend to get out of their office chairs in zero-g. It’s an impossible acting challenge but they do it, somehow, rolling sideways with their arms in the air, and their hair messed up.

But I don’t see those as flaws! They’re actually the hallmarks of invention and passion and imagination and getting-it-done. Blake’s 7, a full space opera with planets and space battles, literally had 50 pounds per episode for special effects (it was budgeted as a non-sci-fi police procedural and had the same VFX budget). Using outside video cameras in Survivors instead of film meant more scenes outdoors, more rehearsals, more varied shots… giving it an energy and look far beyond other shows from 1975 … and it’s all documented. (Is that a BBC thing? A nerd thing? A British thing?) So that has massive appeal.

On a sci-fi level, I like how “hard” a lot of that era is. There’s a certain integrity to it. Red Dwarf is a comedy but the rules of the universe around aliens and the Jupiter Mining Corporation are quite consistent and persistent.

There’s a thinking person’s edge to that era too. It’s very political. I’m not from the UK so I never had to live under Thatcher but gosh she inspired some great science fiction. 1980s Judge Dredd is so pure and dark and satirical. I love it.

Finally, perhaps the defining feature of that era is how theatrical it is. It’s got drama. The actors especially elevate the material a lot. It’s got a lot to like!

Visibility is a perennial issue for indie games. What’s the solution?

Make a game that people want. Visibility is so much easier when people want the game. So it starts with “who am I making this game for?”. A rabbit-collectingcarrots platformer is so broad it ends up not being for anyone. “Girls who love ponies”, “gays who love brunch”, “New Zealanders who like drugs” … know who it’s for, make it for someone.

Get a grip on budget. It hurts but it’s worth it. Before a game (after a bit of prototyping) I sit down and work out a realistic sales estimate and then calculate how much development that pays for, worst case. Then that is my time estimate to guide development. I have done both – a budgeted small version of a passion project and an unbudgeted sprawling epic version of a passion project and the intrinsic satisfaction was the same whether it was six months or six years. It came from completion, not size or duration. That cool feature? Put it in the sequel.

Third, community building is so important. Bringing gamers with you on the next project. I’m terrible at it. I have no answers really. I have almost zero patience for it and it feels fake and forced to me.

How long have you been developing Liberation and what has the process been like?

Liberation took six months to make. In the last 18 months I have completely changed my process. It’s almost like I went back to school. I know I can make a good game so the goal for me on Liberation was to make a good game in a timely, predictable manner. I was lucky in that I could see the game in my mind’s eye and it was very smooth. I use open source software such as Linux and Godot and it’s a really clean pipeline now.

What’s been the biggest challenge?

Space games are hard! Not in a technical sense but in a genre sense. People have very specific expectations for them. I find modern space sims very serious, very realistic, and with too many details and options. In most endeavours I believe you should keep removing things until there’s nothing left to remove and my coding is the equivalent of painting with large brush strokes. Those stylistic considerations clash with space sim expectations. So in that regard, I made a lot of tough design decisions for Liberation. I have to hope players come along with me for it. I also have to resist giving players what they say they want when I’m pretty sure it would dilute the things that make Liberation special. But I do want to give players what they want!

Has it been worthwhile?

A thousand times YES. So much of my life has been about denying myself what I like. For decades I was like “I could never make my version of Elite” or “I could never make a game about Metal Mickey” but with Liberation I just threw it all in there and it’s glorious. I got it done. Finishing is the most underrated skill.

Given that most of your previous games have been adventures, how have you enjoyed making a space shooter? Is it a genre you might return to?

Oh yes, I feel “liberated” in a way. For every big decision I made on Liberation there was an element of “what if?” … so I have a draft folder full of notes for Liberation 2. It would be so different but the same – the best kind of follow up. I was surprised with how much I fell in love with the metal aspect of Liberation. It’s primarily a bright retro space sim game but there are moments where it whacks you through the screen. I love that. Liberation 2 would be a full punch to the face.

MCV/DEVELOP News, events, research and jobs from the games industry

MCV/DEVELOP News, events, research and jobs from the games industry